CLASS

IS ABOUT...

2.jpg)

.jpg)

2.jpg)

197x132.jpg)

179x271.jpg)

195x132.jpg)

Installation view of Classless Society exhibition, Tang Museum

Installation view of Classless Society exhibition, Tang Museum

Installation view of Classless Society exhibition, Tang Museum

Installation view of Classless Society exhibition, Tang Museum

Installation view of Classless Society exhibition, Tang Museum

Installation view of Classless Society exhibition, Tang Museum

Tina Barney, The Reunion, 1999, chromogenic color print, 48 x 60 inches, copyright Tina Barney, courtesy of Janet Borden, Inc., New York

Born into an affluent New York City family, photographer Tina Barney (b. 1945) makes large-scale photographs of her family and friends in affluent areas of Long Island and New England. Barney's images reveal the subtle dynamics of wealth and success through her subjects' posture, dress, attitudes, and expressions. Often candid, Barney's works depict both lavish gatherings and the daily lives of her family members. Her ongoing studies of her own family reveal how inherited wealth affects multiple generations of people.

Cris Bruch, Roller Roaster, 1985, steel shopping cart, grill, and mixed media, 39 x 55 x 39 inches, Yale University Art Gallery, Janet and Simeon Braugin Fund

In his work from the late 1980s and early 1990s, Cris Bruch (b. 1957) mixed performance and sculpture to explore American consumer culture and economic disparity. During the recession of the late 1980s, with a swiftly gentrifying Seattle as a backdrop, Bruch roasted onions on his Roller Roaster, a sculpture that echoes homeless people's shopping carts loaded with their possessions. To highlight alternative economic possibilities, Bruch stationed himself outside upscale restaurants and bartered onions with passersby in performances called Vegetable Currency.

James Casebere, Landscape with Houses (Dutchess County, NY) #3, 2010, digital chromogenic print mounted on dibond, 44 x 55 inches, collection of Steven and Lisa Goldglit, copyright James Casebere, image courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

Photographer James Casebere (b. 1953) examines the increase in the suburban population since the late twentieth century and its effect on the American landscape and psyche. Casebere's large-format photographs of suburban upper-middle-class housing actually depict landscapes meticulously designed and produced in the studio, using information drawn from architecture, art history, and cinema. These artificial vistas of "idyllic" subdivisions display the effects of class on both how and where we live.

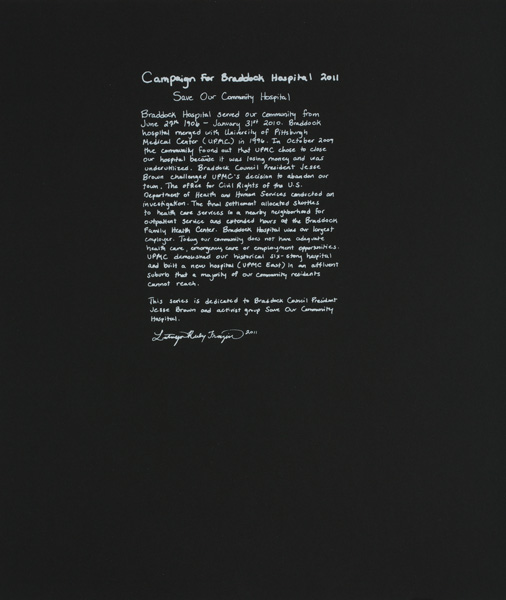

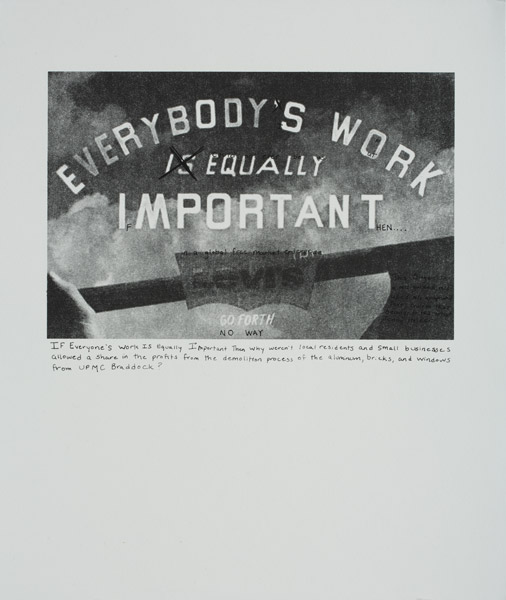

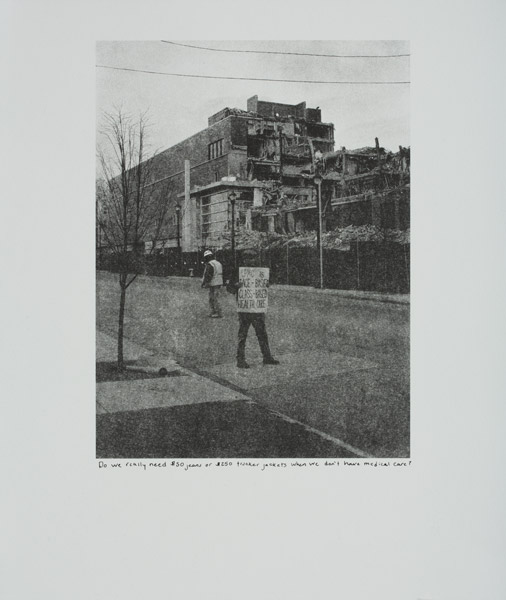

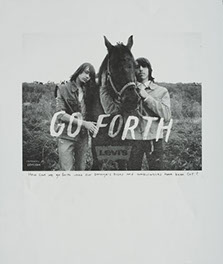

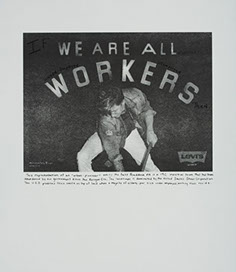

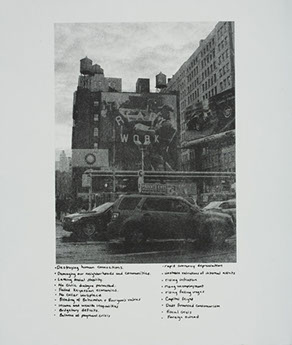

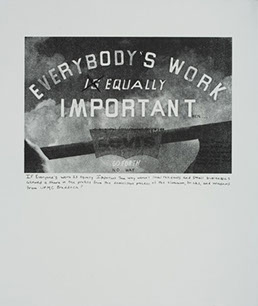

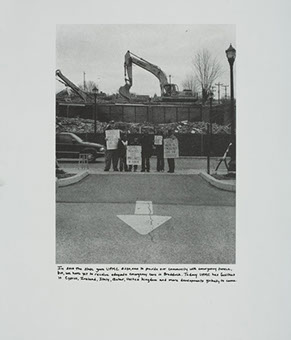

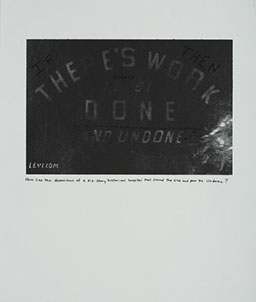

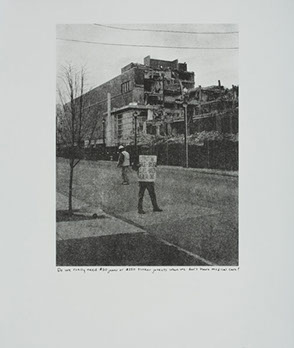

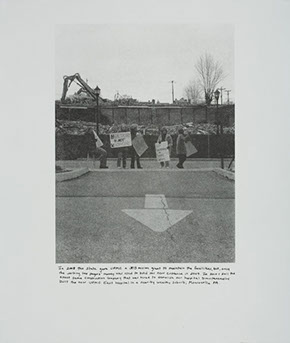

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011, suite of 12 photolithographs and silkscreen prints, 17 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist

Photographer and media artist LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) combines social documentary and portraiture to examine the human casualties of economic decline. Raised in the decaying steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier focuses her photography on the town's working-class population and Braddock's change from an industrial center to a place abandoned by industry and wealth. This portfolio examines the town's struggle with access to health care after its hospital closed in 2010. Unraveling reality from fantasy, it critiques a Levi's advertisement campaign that used the town as its source material.

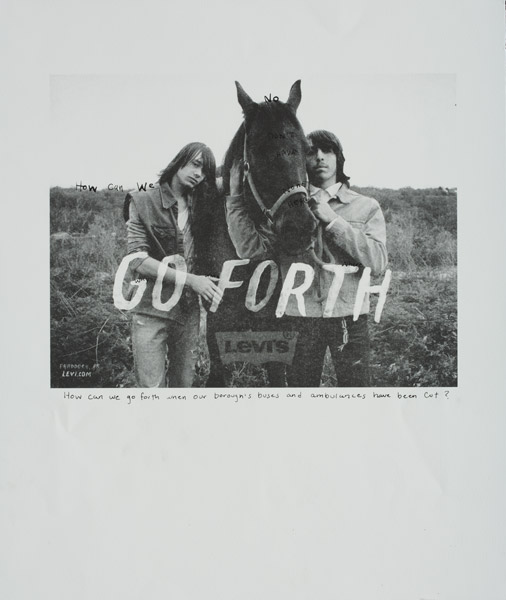

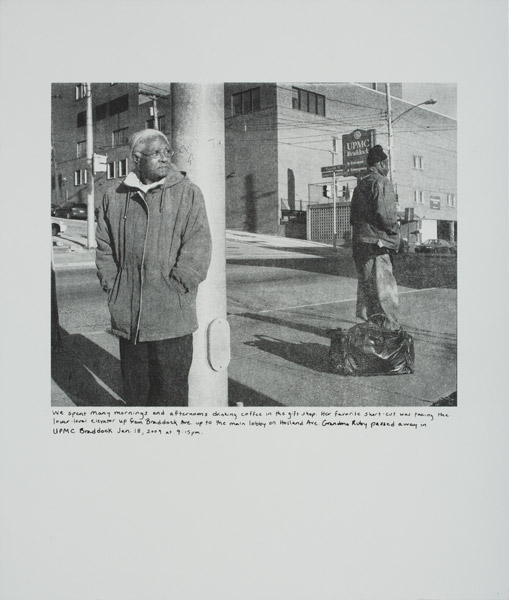

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011, suite of 12 photolithographs and silkscreen prints, 17 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist

Photographer and media artist LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) combines social documentary and portraiture to examine the human casualties of economic decline. Raised in the decaying steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier focuses her photography on the town's working-class population and Braddock's change from an industrial center to a place abandoned by industry and wealth. This portfolio examines the town's struggle with access to health care after its hospital closed in 2010. Unraveling reality from fantasy, it critiques a Levi's advertisement campaign that used the town as its source material.

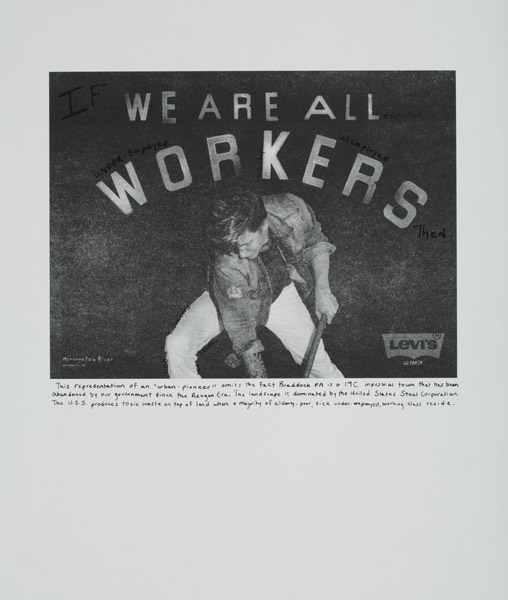

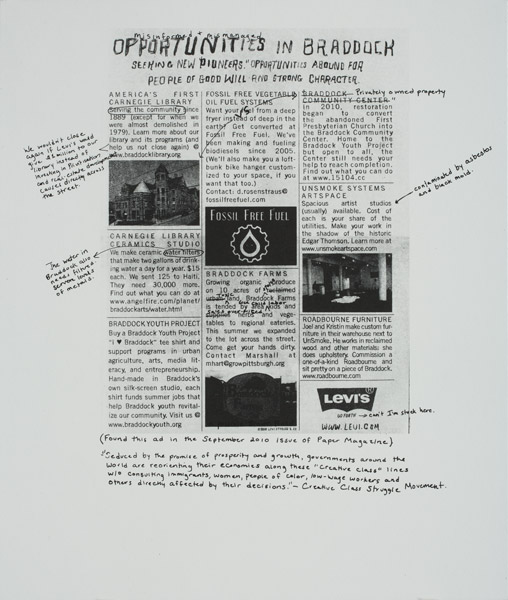

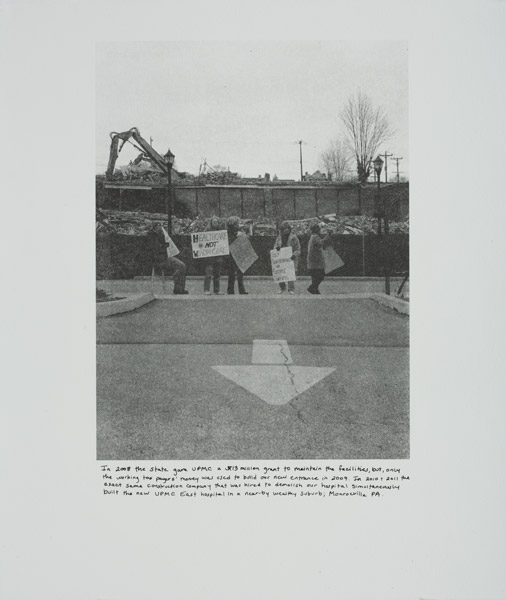

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011, suite of 12 photolithographs and silkscreen prints, 17 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist

Photographer and media artist LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) combines social documentary and portraiture to examine the human casualties of economic decline. Raised in the decaying steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier focuses her photography on the town's working-class population and Braddock's change from an industrial center to a place abandoned by industry and wealth. This portfolio examines the town's struggle with access to health care after its hospital closed in 2010. Unraveling reality from fantasy, it critiques a Levi's advertisement campaign that used the town as its source material.

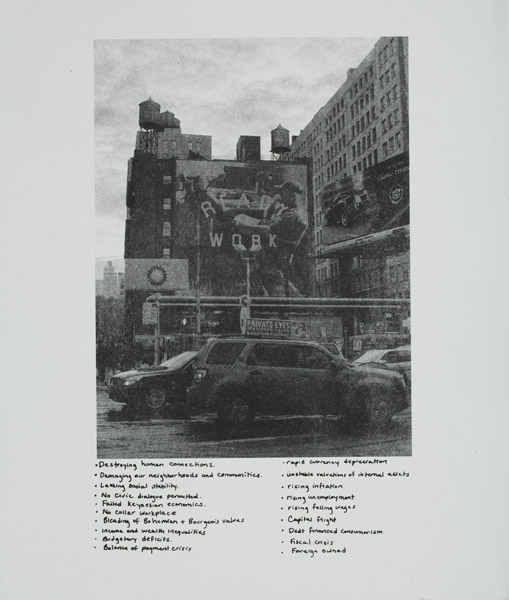

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011, suite of 12 photolithographs and silkscreen prints, 17 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist

Photographer and media artist LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) combines social documentary and portraiture to examine the human casualties of economic decline. Raised in the decaying steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier focuses her photography on the town's working-class population and Braddock's change from an industrial center to a place abandoned by industry and wealth. This portfolio examines the town's struggle with access to health care after its hospital closed in 2010. Unraveling reality from fantasy, it critiques a Levi's advertisement campaign that used the town as its source material.

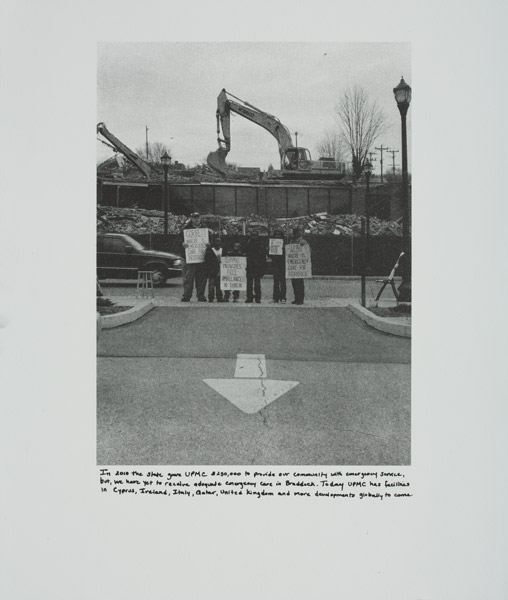

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011, suite of 12 photolithographs and silkscreen prints, 17 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist

Photographer and media artist LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) combines social documentary and portraiture to examine the human casualties of economic decline. Raised in the decaying steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier focuses her photography on the town's working-class population and Braddock's change from an industrial center to a place abandoned by industry and wealth. This portfolio examines the town's struggle with access to health care after its hospital closed in 2010. Unraveling reality from fantasy, it critiques a Levi's advertisement campaign that used the town as its source material.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011, suite of 12 photolithographs and silkscreen prints, 17 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist

Photographer and media artist LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) combines social documentary and portraiture to examine the human casualties of economic decline. Raised in the decaying steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier focuses her photography on the town's working-class population and Braddock's change from an industrial center to a place abandoned by industry and wealth. This portfolio examines the town's struggle with access to health care after its hospital closed in 2010. Unraveling reality from fantasy, it critiques a Levi's advertisement campaign that used the town as its source material.

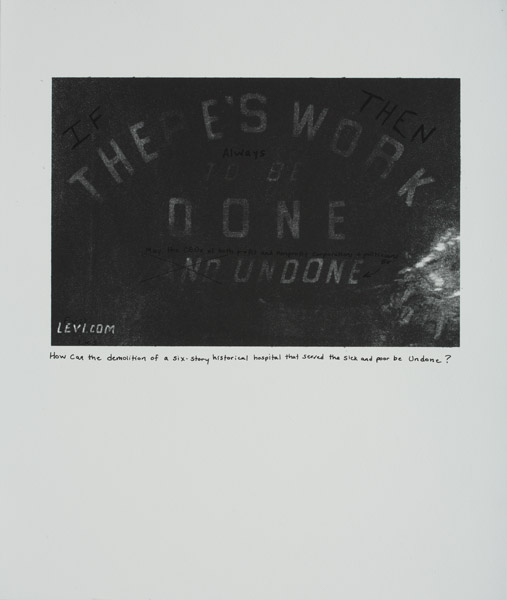

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011, suite of 12 photolithographs and silkscreen prints, 17 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist

Photographer and media artist LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) combines social documentary and portraiture to examine the human casualties of economic decline. Raised in the decaying steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier focuses her photography on the town's working-class population and Braddock's change from an industrial center to a place abandoned by industry and wealth. This portfolio examines the town's struggle with access to health care after its hospital closed in 2010. Unraveling reality from fantasy, it critiques a Levi's advertisement campaign that used the town as its source material.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011, suite of 12 photolithographs and silkscreen prints, 17 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist

Photographer and media artist LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) combines social documentary and portraiture to examine the human casualties of economic decline. Raised in the decaying steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier focuses her photography on the town's working-class population and Braddock's change from an industrial center to a place abandoned by industry and wealth. This portfolio examines the town's struggle with access to health care after its hospital closed in 2010. Unraveling reality from fantasy, it critiques a Levi's advertisement campaign that used the town as its source material.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011, suite of 12 photolithographs and silkscreen prints, 17 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist

Photographer and media artist LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) combines social documentary and portraiture to examine the human casualties of economic decline. Raised in the decaying steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier focuses her photography on the town's working-class population and Braddock's change from an industrial center to a place abandoned by industry and wealth. This portfolio examines the town's struggle with access to health care after its hospital closed in 2010. Unraveling reality from fantasy, it critiques a Levi's advertisement campaign that used the town as its source material.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011, suite of 12 photolithographs and silkscreen prints, 17 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist

Photographer and media artist LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) combines social documentary and portraiture to examine the human casualties of economic decline. Raised in the decaying steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier focuses her photography on the town's working-class population and Braddock's change from an industrial center to a place abandoned by industry and wealth. This portfolio examines the town's struggle with access to health care after its hospital closed in 2010. Unraveling reality from fantasy, it critiques a Levi's advertisement campaign that used the town as its source material.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011, suite of 12 photolithographs and silkscreen prints, 17 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist

Photographer and media artist LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) combines social documentary and portraiture to examine the human casualties of economic decline. Raised in the decaying steel town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier focuses her photography on the town's working-class population and Braddock's change from an industrial center to a place abandoned by industry and wealth. This portfolio examines the town's struggle with access to health care after its hospital closed in 2010. Unraveling reality from fantasy, it critiques a Levi's advertisement campaign that used the town as its source material.

Andrea Funk, Untitled (for Local 14 Teamsters), t-shirt quilt, 51 x 57 1/2 inches, American Labor Museum/ Botto House National Landmark, Haledon, New Jersey

Andrea Funk, Untitled (for Local 1040 (CWA)), t-shirt quilt, 51 x 51 inches, American Labor Museum/ Botto House National Landmark, Haledon, New Jersey

Andrea Funk, Untitled (for Lorenzo), t-shirt quilt, 58 x 57 1/2 inches, American Labor Museum/ Botto House National Landmark, Haledon, New Jersey

Andrea Funk, Untitled (for United Together), t-shirt quilt, 50 1/2 x 58 1/2 inches, American Labor Museum/ Botto House National Landmark, Haledon, New Jersey

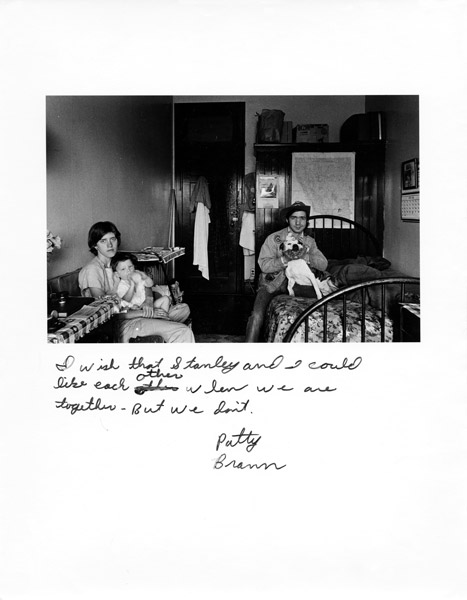

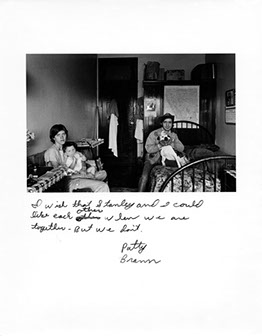

Jim Goldberg, I wish that Stanley and I could like each other, from Rich and Poor, 1979, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

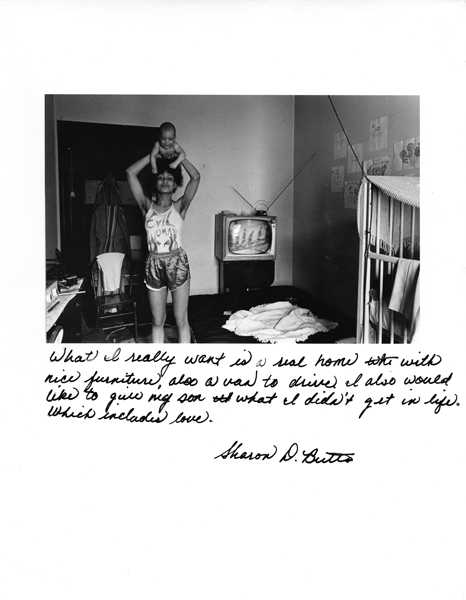

Jim Goldberg, What I really want is a real home, from Rich and Poor, 1979/1980, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

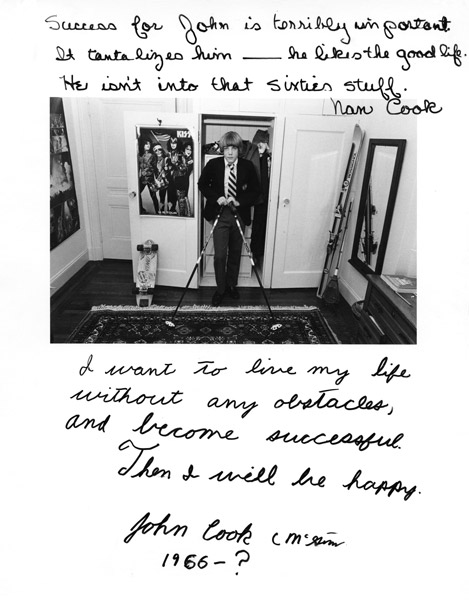

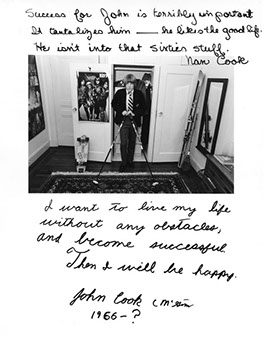

Jim Goldberg, Success for John is terribly important, from Rich and Poor, 1982, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

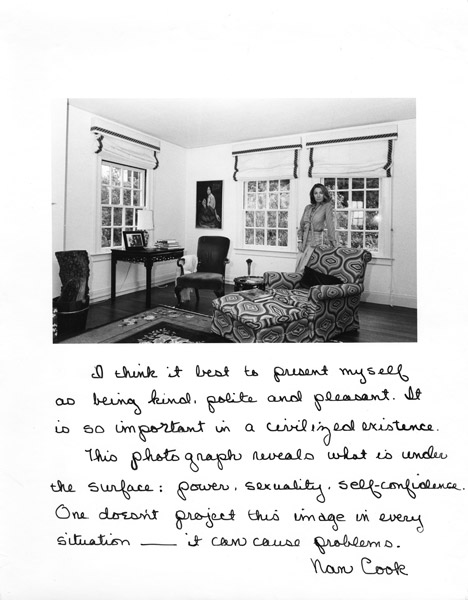

Jim Goldberg, I think it best to present myself as being kind, from Rich and Poor, 1982/85, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

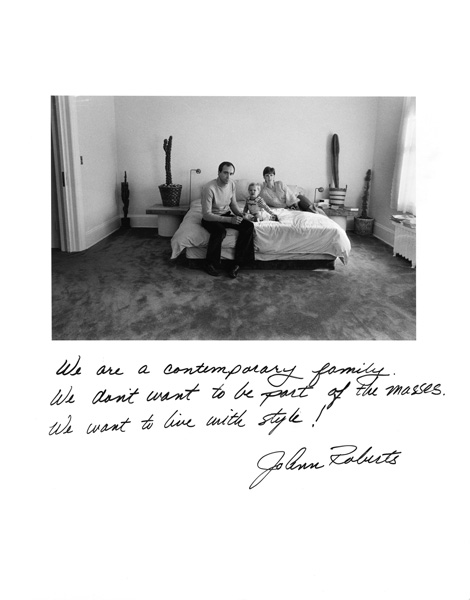

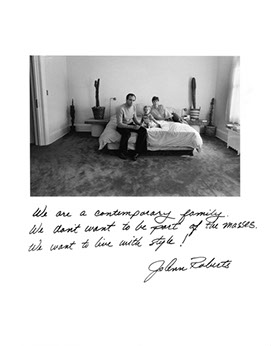

Jim Goldberg, We are a contemporary family, from Rich and Poor, 1981, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

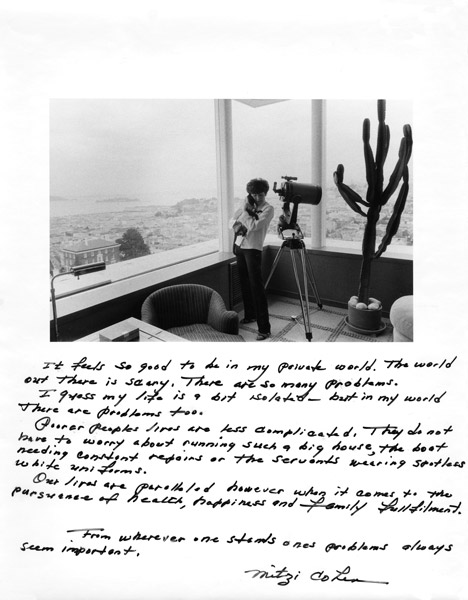

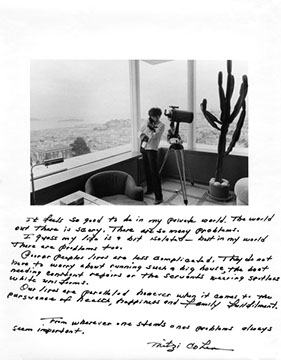

Jim Goldberg, It feels so good to be in my private world, from Rich and Poor, 1982/84, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

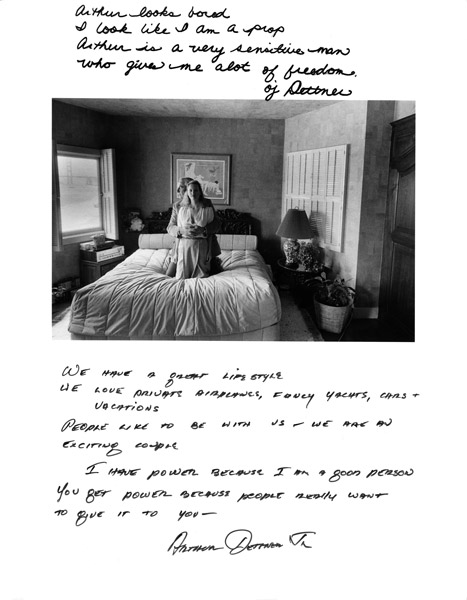

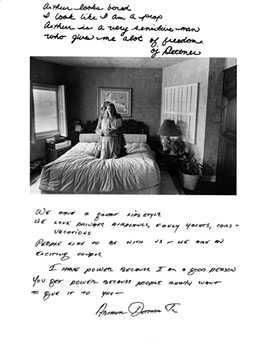

Jim Goldberg, Arthur looks bored, from Rich and Poor, 1980/83, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen

Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

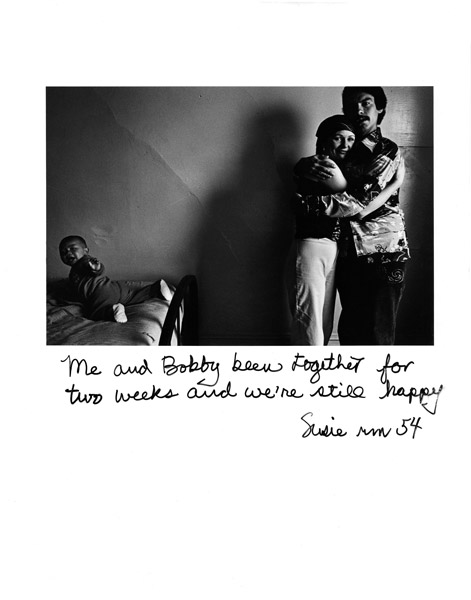

Jim Goldberg, Me and Bobby been together for two weeks, from Rich and Poor, 1977, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

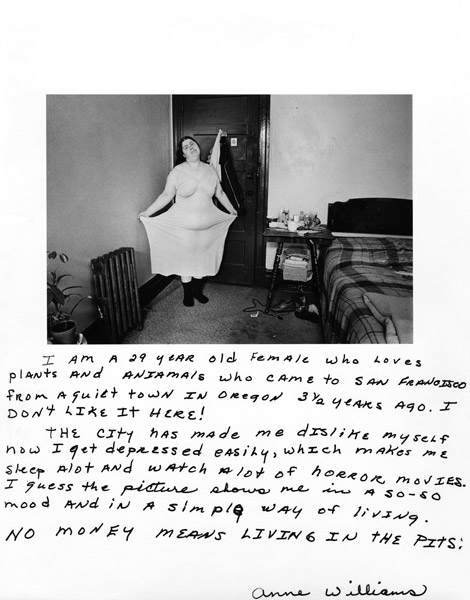

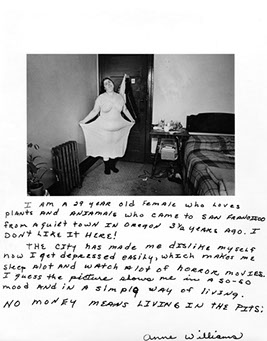

Jim Goldberg, I am a 29 year old female, from Rich and Poor, 1978/85, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

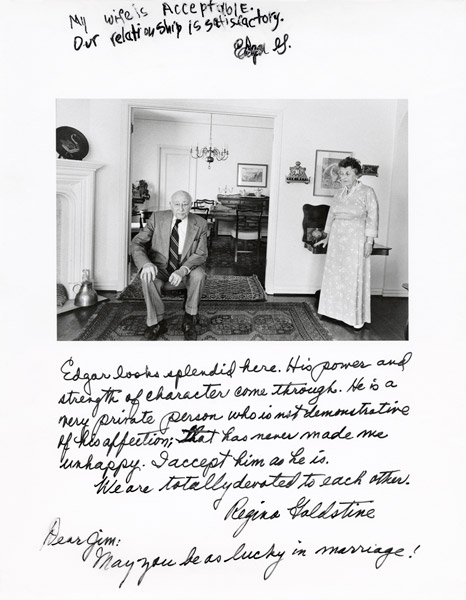

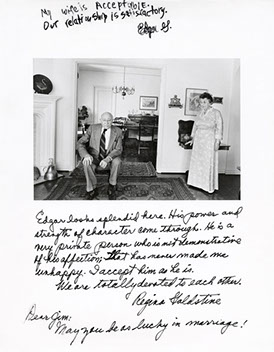

Jim Goldberg, My wife is acceptable, from Rich and Poor, 1981/85, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

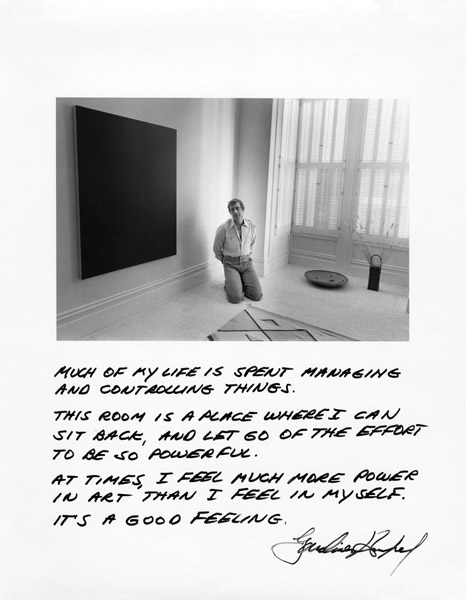

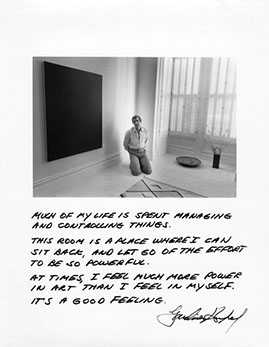

Jim Goldberg, Much of my life is spent managing and controlling things, from Rich and Poor, 1980/82, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

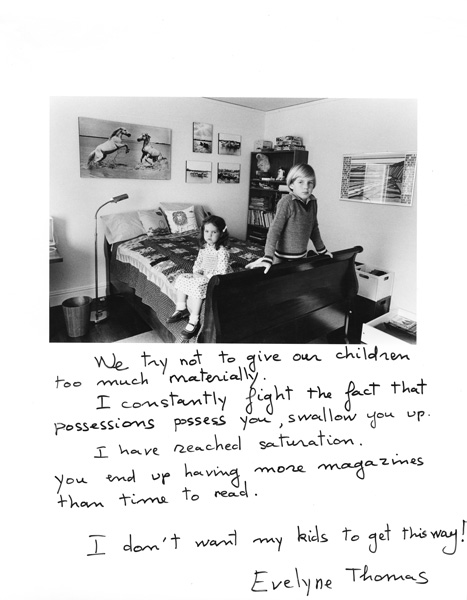

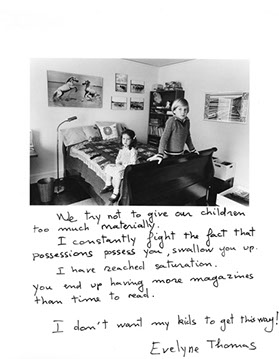

Jim Goldberg, We try not to give our children too much materially, from Rich and Poor, 1981/83, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

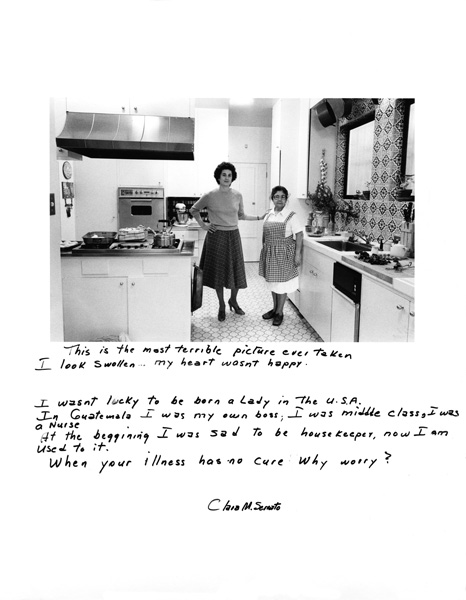

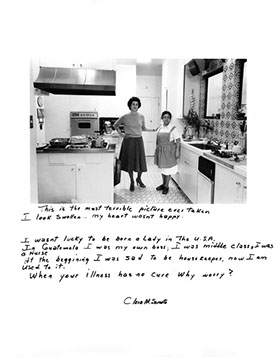

Jim Goldberg, This is the most terrible picture ever taken, from Rich and Poor, 1984, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

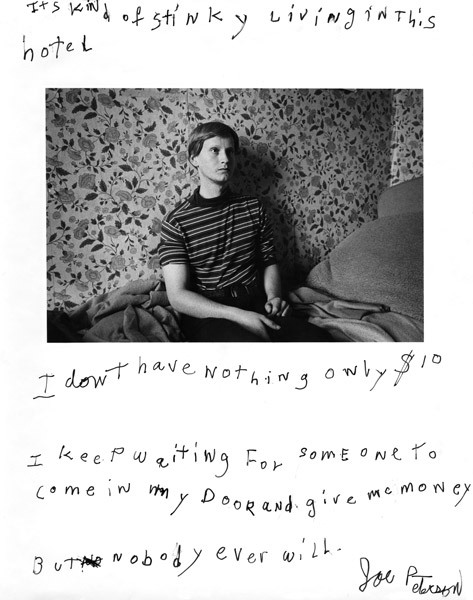

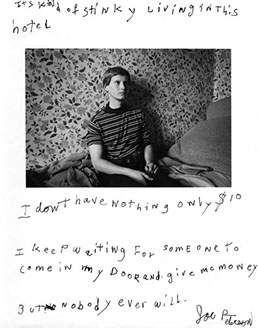

Jim Goldberg, Its kind of stinky living in this hotel, from Rich and Poor, 1984/85, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

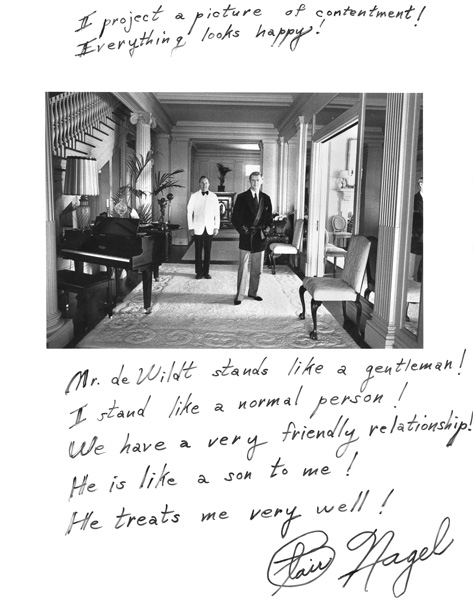

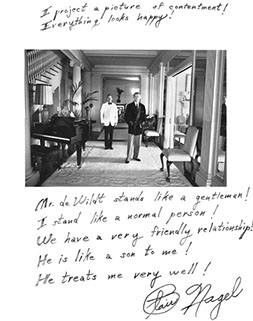

Jim Goldberg, I project a picture of contentment, from Rich and Poor, 1982, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

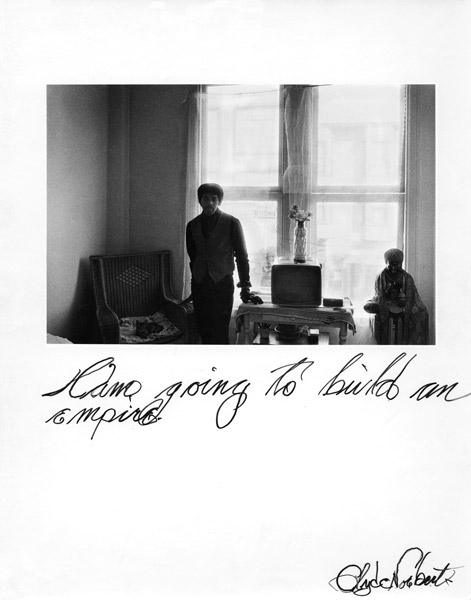

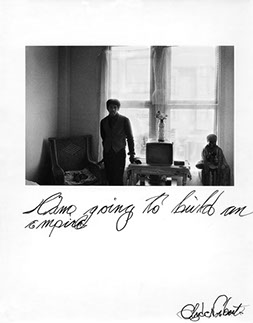

Jim Goldberg, I am going to build an empire, from Rich and Poor, 1977/78, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

In his series Rich and Poor, photographer Jim Goldberg (b. 1953) presents photographs of both wealthy and poor people, below which the subjects have handwritten their own notes, addressing their lives and hopes and revealing the injuries, human frailties, and self-delusions wrought by the class system in the United States. Taken together, Goldberg's images and his subjects' texts present a powerful and often bleak picture of how extremes of poverty and wealth affect the human psyche.

Derrick Jones, still of 631, 2008, video, 9:18 minutes, courtesy DAJones Film

Youngstown, Ohio-born filmmaker Derrick Jones documents social injustices and examines the effects of economic change on communities. In 631, Jones presents the highs and lows his own family experienced in his childhood home. Drawing its title from the home's street number, Jones's film deals with abandoned property in underprivileged communities and explores class through his personal story of downward mobility. The film has been screened at numerous film festivals, including the Cannes Film Festival and the Langston Hughes African-American Film Festival.

Steve Lambert, It's About Power, 2011, laser-cut acrylic, wood, lights, 36 x 36 inches, courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery,

Los Angeles

Steve Lambert (b. 1976) works in performance, sculpture, internet art, and other media. His often-participatory art asks viewers to assess the society in which they live and explores the power structures in American society. Founder of the Anti-Advertising Agency, Lambert uses the language, look, and feel of advertising to explore issues of consumption, capitalism, class, and media. Deceptively simple, Lambert's "signs" invite viewers into a larger conversation about the efficacy of American social structures.

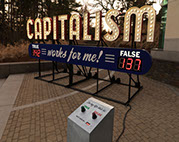

Steve Lambert, Capitalism Works For Me! True/False, 2011, aluminum, lights, wood, electronics, 20 x 9 x 7 feet, courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles

Steve Lambert (b. 1976) works in performance, sculpture, internet art, and other media. His often-participatory art asks viewers to assess the society in which they live and explores the power structures in American society. Founder of the Anti-Advertising Agency, Lambert uses the language, look, and feel of advertising to explore issues of consumption, capitalism, class, and media. Deceptively simple, Lambert's "signs" invite viewers into a larger conversation about the efficacy of American social structures.

Nikki S. Lee, The Ohio Project (6), 1999, fujiflex print, 21 1/4 x 28 1/4 inches, collection of Leslie Tonkonow and Klaus Ottmann, copyright 1999 Nikki S. Lee, image courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Nikki S. Lee (b. 1970) is a performance artist and photographer. By assuming the roles of a yuppie, punk, schoolgirl, senior citizen, and dancer, among others, Lee explores identity, its malleability, and its constructed nature. After acclimating to each identity group and spending time with it, Lee asks its members to take her picture with others in the group, documenting her time within that community. In her series The Ohio Project and The Yuppie Project, she examines how class is both constructed and enacted on a daily basis.

Nikki S. Lee, The Ohio Project (7), 1999, fujiflex print, 28 1/4 x 21 1/4 inches, Ann and Mel Schaffer Family Collection, copyright 1999 Nikki S. Lee, image courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Nikki S. Lee (b. 1970) is a performance artist and photographer. By assuming the roles of a yuppie, punk, schoolgirl, senior citizen, and dancer, among others, Lee explores identity, its malleability, and its constructed nature. After acclimating to each identity group and spending time with it, Lee asks its members to take her picture with others in the group, documenting her time within that community. In her series The Ohio Project and The Yuppie Project, she examines how class is both constructed and enacted on a daily basis.

Nikki S. Lee, Yuppie Project (4), 1998, fujiflex print, 21 1/4 x 28 1/4 inches, Collection of Leslie Tonkonow and Klaus Ottmann, copyright 1998 Nikki S. Lee, image courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Nikki S. Lee (b. 1970) is a performance artist and photographer. By assuming the roles of a yuppie, punk, schoolgirl, senior citizen, and dancer, among others, Lee explores identity, its malleability, and its constructed nature. After acclimating to each identity group and spending time with it, Lee asks its members to take her picture with others in the group, documenting her time within that community. In her series The Ohio Project and The Yuppie Project, she examines how class is both constructed and enacted on a daily basis.

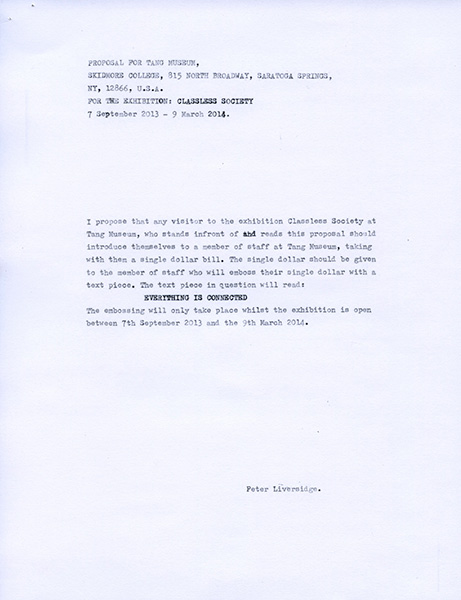

Peter Liversidge, Proposals for the Tang Museum, 2013, typewriter carbon on paper, 14 pages, each 8 1/2 x 11 inches, courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

Conceptual artist Peter Liversidge (b. 1973) creates proposals for performances and artworks across a wide range of media. Ranging from the possible to the hypothetical, Liversidge's proposals, typed on an old manual typewriter, hang in the exhibition; over the course of Classless Society, selected proposals will become realized. Liversidge's proposals actively engage the place for which he creates them, often highlighting that community's economic disparity and social issues. Liversidge believes his works require the viewers' unique interpretations to complete them, and his proposals often ask viewers to interact with others or their surroundings in ways designed to stimulate new perceptions and connections.

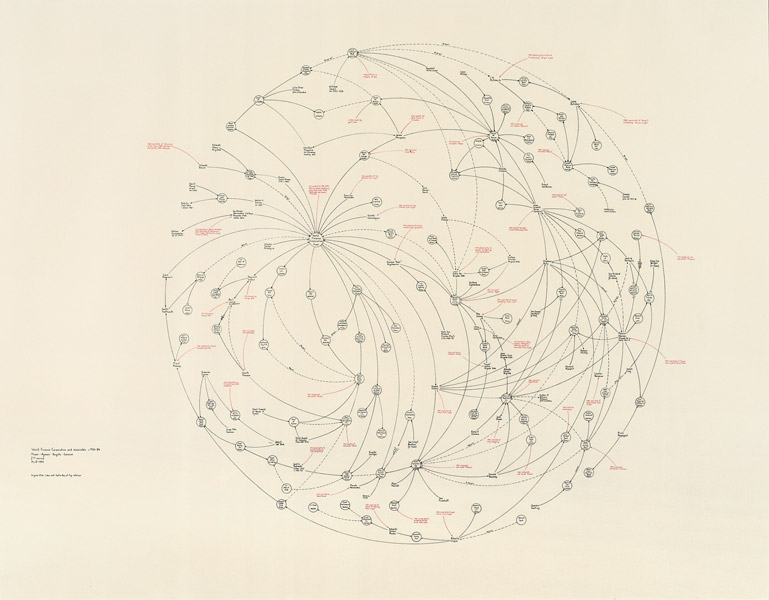

Mark Lombardi, World Finance Corporation and Associates, ca. 1970-84: Miami, Ajman, and Bogota-Caracas (Brigada 2506: Cuban Anti-Castro Bay of Pigs Veteran) (7th Version), 1999, colored pencil and graphite on paper, 69 1/8 x 84 inches, private collection, image courtesy of Pierogi and Donald Lomabardi, photography by John Berens

Mark Lombardi (1951-2000) created carefully planned drawings that document extensive networks of influence, money, and power, attempting to clarify the often complicated financial connections among individuals, governments, and other institutions. His extensively researched diagrammatic compositions establish and illustrate connections between key figures involved in political and financial scandals. Working as a library archivist for most of his life, Lombardi began illustrating his research just six years before his death. In 2012, German director Mareike Wegener released a documentary on Lombardi, Mark Lombardi: Death-Defying Acts of Art and Conspiracy.

Irving Norman, Meeting of the Elders 3, 1977, oil on canvas, 90 x 100 inches, Tang Teaching Museum on extended loan from The Collection of Marlene and Alan Gilbert, image courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York, NY

After emigrating from Poland to the United States in 1923, Irving Norman (1906-1989) eventually settled near San Francisco, where he lived and worked for most of his life. His large-scale paintings critiqued contemporary life as well as consumer culture and other elements of American society. As an immigrant, Norman offered a perspective on American culture as both an outsider and a citizen of the society he critiqued. In Meeting of the Elders 3, Norman focused on currency and its link to power and bureaucracy. The richly detailed painting hints at the interconnected threads of slavery, wage theft, the spoils of war, and the human price of boardroom machinations that manipulate facts and figures to benefit the few at the expense of the many.

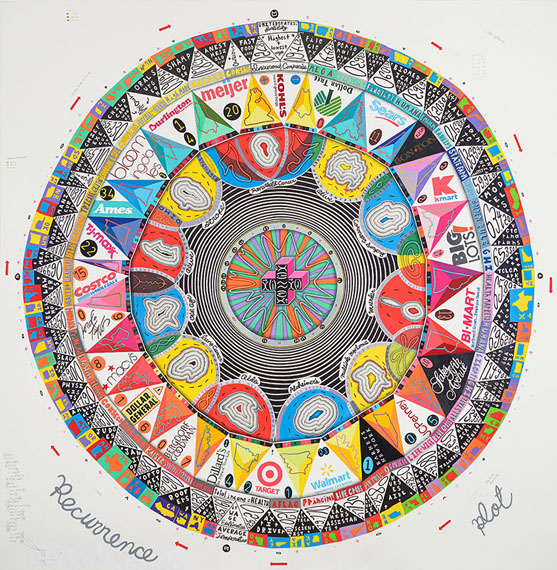

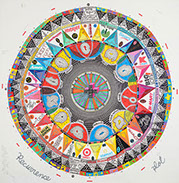

John O'Connor, A Recurrence Plot, 2013, colored pencil, graphite, and acrylic on paper, 71 1/2 x 69 3/4 inches, courtesy of the artist and Pierogi Gallery

John O'Connor (b. 1972) is known for his large-scale drawings in which he creates psychedelic patterns from carefully chosen and often self-compiled data. Inspired by scientific discoveries, news headlines, and phenomena such as lottery success or weight fluctuation, O’Connor presents these data sets in novel ways, building new relationships between them. In A Recurrence Plot, commissioned for Classless Society, O'Connor attempts to measure class in a tangible, visual way. The work was inspired by a conversation between the artist and a doctor in which the doctor equated a person's healthcare rights with a shopping experience. Organized like a diagram of the earth's layers from crust to core, the drawing maps a person's life cycle from birth to death through a class-inflected lens.

Michael Patterson-Carver, Boston, 2009, ink, pencil, watercolor on paper, 15 x 20 inches, Ann and Mel Schaffer Family Collection, image courtesy of Laurel Gitlen, New York

Michael Patterson-Carver (b. 1958) brings to light issues of social injustice, whether environmental, political, or economic. His colorful drawings illuminate both the need for protest and protests themselves, functioning as a call to action. Patterson-Carver illuminates current and historical issues of political class-based struggle and employs seemingly contradictory senses of dark humor and optimism. Patterson-Carver's connection to economic disparity is also personal: he began his art career by selling his work on the sidewalks of Portland, Oregon, when he was homeless.

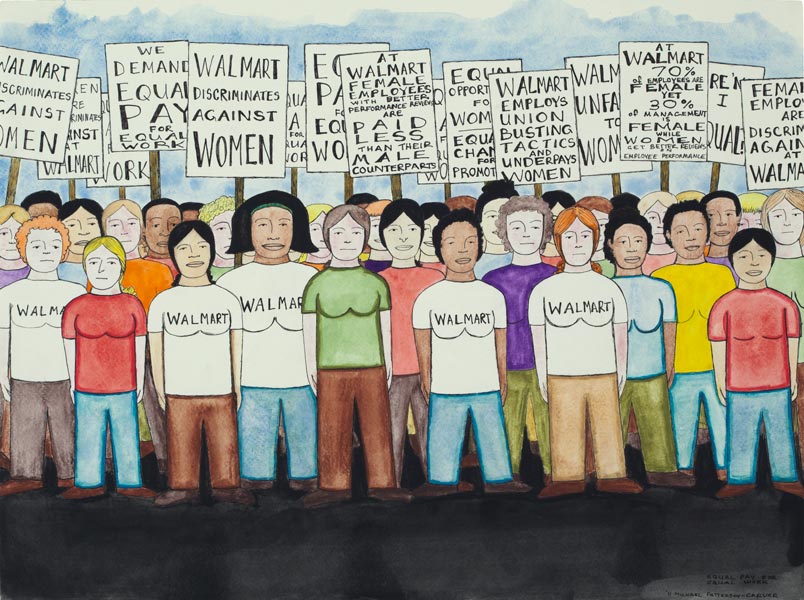

Michael Patterson-Carver, Equal Pay for Equal Work, 2011, ink, pencil, watercolor on paper, 15 x 20 inches, courtesy of the artist and Laurel Gitlen, New York

Michael Patterson-Carver (b. 1958) brings to light issues of social injustice, whether environmental, political, or economic. His colorful drawings illuminate both the need for protest and protests themselves, functioning as a call to action. Patterson-Carver illuminates current and historical issues of political class-based struggle and employs seemingly contradictory senses of dark humor and optimism. Patterson-Carver's connection to economic disparity is also personal: he began his art career by selling his work on the sidewalks of Portland, Oregon, when he was homeless.

Doug Rickard, #40.805716, Bronx, NY (2007), from A New American Picture, 2011, archival pigment print, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

Photographer Doug Rickard (b. 1968) creates images of some of the nation's poorest cities and towns. In his series A New American Picture, Rickard employs images from Google Street View to create a portrait of Great Recession-era America. Rickard carefully selected the images in this series to bring to light the American landscape and its economic segregation. Motivated by the histories of race and class in the United States, Rickard used Street View to survey significant cities and locations in the history of the Civil Rights Movement, such as Selma and Birmingham, Alabama. As the series developed, he deliberately chose places identified by realtors' websites as "bad neighborhoods," "areas to avoid," and other codes for places inhabited by the poor and underclass.

Doug Rickard, #104.573110, Lovington, NM (2008), from A New American Picture, 2009, archival pigment print, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

Photographer Doug Rickard (b. 1968) creates images of some of the nation's poorest cities and towns. In his series A New American Picture, Rickard employs images from Google Street View to create a portrait of Great Recession-era America. Rickard carefully selected the images in this series to bring to light the American landscape and its economic segregation. Motivated by the histories of race and class in the United States, Rickard used Street View to survey significant cities and locations in the history of the Civil Rights Movement, such as Selma and Birmingham, Alabama. As the series developed, he deliberately chose places identified by realtors' websites as "bad neighborhoods," "areas to avoid," and other codes for places inhabited by the poor and underclass.

Doug Rickard, #82.948842, Detroit, MI (2009), from A New American Picture, 2010, archival pigment print, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

Photographer Doug Rickard (b. 1968) creates images of some of the nation's poorest cities and towns. In his series A New American Picture, Rickard employs images from Google Street View to create a portrait of Great Recession-era America. Rickard carefully selected the images in this series to bring to light the American landscape and its economic segregation. Motivated by the histories of race and class in the United States, Rickard used Street View to survey significant cities and locations in the history of the Civil Rights Movement, such as Selma and Birmingham, Alabama. As the series developed, he deliberately chose places identified by realtors' websites as "bad neighborhoods," "areas to avoid," and other codes for places inhabited by the poor and underclass.

Doug Rickard, #27.144277, Okeechobee, FL (2008), from A New American Picture, 2011, archival pigment print, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

Photographer Doug Rickard (b. 1968) creates images of some of the nation's poorest cities and towns. In his series A New American Picture, Rickard employs images from Google Street View to create a portrait of Great Recession-era America. Rickard carefully selected the images in this series to bring to light the American landscape and its economic segregation. Motivated by the histories of race and class in the United States, Rickard used Street View to survey significant cities and locations in the history of the Civil Rights Movement, such as Selma and Birmingham, Alabama. As the series developed, he deliberately chose places identified by realtors' websites as "bad neighborhoods," "areas to avoid," and other codes for places inhabited by the poor and underclass.

Doug Rickard, #42.318327, Detroit, MI (2009), from A New American Picture, 2010, archival pigment print, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

Photographer Doug Rickard (b. 1968) creates images of some of the nation's poorest cities and towns. In his series A New American Picture, Rickard employs images from Google Street View to create a portrait of Great Recession-era America. Rickard carefully selected the images in this series to bring to light the American landscape and its economic segregation. Motivated by the histories of race and class in the United States, Rickard used Street View to survey significant cities and locations in the history of the Civil Rights Movement, such as Selma and Birmingham, Alabama. As the series developed, he deliberately chose places identified by realtors' websites as "bad neighborhoods," "areas to avoid," and other codes for places inhabited by the poor and underclass.

Doug Rickard, #41.779976, Chicago, IL (2007), from A New American Picture, 2010, archival pigment print, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

Photographer Doug Rickard (b. 1968) creates images of some of the nation's poorest cities and towns. In his series A New American Picture, Rickard employs images from Google Street View to create a portrait of Great Recession-era America. Rickard carefully selected the images in this series to bring to light the American landscape and its economic segregation. Motivated by the histories of race and class in the United States, Rickard used Street View to survey significant cities and locations in the history of the Civil Rights Movement, such as Selma and Birmingham, Alabama. As the series developed, he deliberately chose places identified by realtors' websites as "bad neighborhoods," "areas to avoid," and other codes for places inhabited by the poor and underclass.

Doug Rickard, #41.214669, Chicago, IL (2007), from A New American Picture, 2010, archival pigment print, courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery

Photographer Doug Rickard (b. 1968) creates images of some of the nation's poorest cities and towns. In his series A New American Picture, Rickard employs images from Google Street View to create a portrait of Great Recession-era America. Rickard carefully selected the images in this series to bring to light the American landscape and its economic segregation. Motivated by the histories of race and class in the United States, Rickard used Street View to survey significant cities and locations in the history of the Civil Rights Movement, such as Selma and Birmingham, Alabama. As the series developed, he deliberately chose places identified by realtors' websites as "bad neighborhoods," "areas to avoid," and other codes for places inhabited by the poor and underclass.

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, The Millennium Series #18: Evicted, 2011, mixed media on cardboard, 15 1/4 x 11 1/4 inches, courtesy of ACA Galleries, New York

Aminah Robinson (b. 1940) creates drawings, sculptures, prints, quilts, paintings, and book illustrations that address her community, friends, family, and personal history. Her work is grounded in the African concept of Sankofa - learning from the past in order to move forward. Robinson's Millennium Series uses richly textured collage elements to examine the 2013 razing of her childhood neighborhood, Poindexter Village, one of the first federally funded housing developments in Columbus, Ohio. The works explore the psychological and physical ruptures caused by this event, and the possible outcomes for the community, including homelessness. With the Millennium Series Robinson asks us to consider the larger issue of America's dwindling safety nets.

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, The Millennium Series #17: Manuscript Page, 2011, mixed media on cardboard, 15 x 11 1/2 inches, courtesy of ACA Galleries, New York

Aminah Robinson (b. 1940) creates drawings, sculptures, prints, quilts, paintings, and book illustrations that address her community, friends, family, and personal history. Her work is grounded in the African concept of Sankofa - learning from the past in order to move forward. Robinson's Millennium Series uses richly textured collage elements to examine the 2013 razing of her childhood neighborhood, Poindexter Village, one of the first federally funded housing developments in Columbus, Ohio. The works explore the psychological and physical ruptures caused by this event, and the possible outcomes for the community, including homelessness. With the Millennium Series Robinson asks us to consider the larger issue of America's dwindling safety nets.

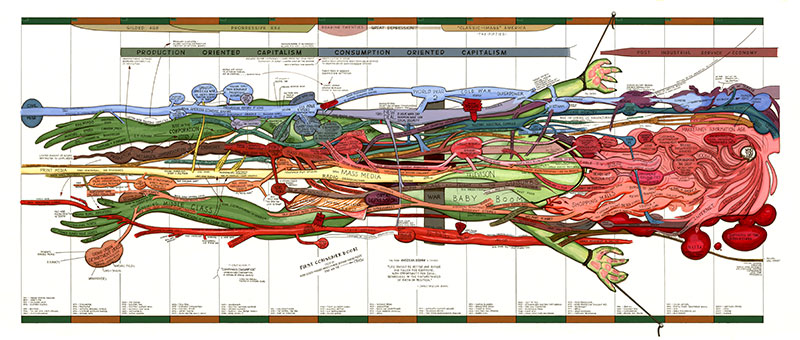

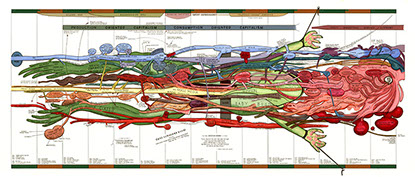

Ward Shelley, Work, Spend, Forget, 2013, acrylic and toner on Mylar, 34 1/4 x 75 inches, courtesy of the artist and Pierogi Gallery

Artist Ward Shelley’s (b. 1950) drawings in toner and acrylic on Mylar explore the histories of social movements through precisely drawn, slightly cartoonish timelines or flow charts. Shelley’s diagrammatic paintings serve as pictorial narratives, unfolding his often complex ideas about the connections and influences between people, social movements, organizations, artistic movements, and more. Shelley likens facts to dots on a graph and his narrative to the curve that connects them and gives isolated data points meaning. Work, Spend, Forget, commissioned for Classless Society, charts the history of twentieth century labor and consumption, tracing a path from production-oriented capitalism to consumption-oriented capitalism.

Jason Simon, VERA, 2003, video, 25 minutes, courtesy of the artist and Callicoon Fine Arts Gallery, New York

The work of film and video artist Jason Simon (b. 1961) highlights the interplay of consumption and culture. Simon's work investigates relationships between our consumption and our understanding of ourselves. In Vera, Simon interviews a woman about her addiction to shopping and her attitudes towards it. Simon's camera stays focused on his subject as she speaks about her desires for both expensive and everyday items, revealing a larger portrait of the intricacies of American consumer culture.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Touch Sanitation Performance, 1977-1980, "Handshake Ritual" with workers of New York City Department of Sanitation, color photograph, 60 x 90 inches, courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

Mierle Ukeles (b. 1939) is a "maintenance artist," best known for her feminist and service-oriented performance, installation, and video art. In 1977 Ukeles became the artist in residence at New York City's Department of Sanitation, a position she continues to hold. The Maintenance Manifesto,1969! typifies Ukeles' interest in maintenance as "keeping New York City alive," which culminated in her public art piece Touch Sanitation. This eleven-month project involved shaking hands with every New York City sanitation worker, talking with them, and thanking them for their work. Through this process, she reveals the way societies often equate workers with the work they do. Ukeles directly counters the notion of "garbage men" as de facto "untouchables" by publicly valuing them and embracing their work. .

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, The Social Mirror, 1983, mirror covered sanitation truck, 28 feet, 2 inches x 8 feet, 4 inches x 10 feet, 6 inches, courtesy of New York City Department of Sanitation and the artist, image courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

Mierle Ukeles (b. 1939) is a "maintenance artist," best known for her feminist and service-oriented performance, installation, and video art. In 1977 Ukeles became the artist in residence at New York City's Department of Sanitation, a position she continues to hold. The Maintenance Manifesto,1969! typifies Ukeles' interest in maintenance as "keeping New York City alive," which culminated in her public art piece Touch Sanitation. This eleven-month project involved shaking hands with every New York City sanitation worker, talking with them, and thanking them for their work. Through this process, she reveals the way societies often equate workers with the work they do. Ukeles directly counters the notion of "garbage men" as de facto "untouchables" by publicly valuing them and embracing their work.

Carrie Mae Weems, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2006, digital chromogenic print, 73 x 61 inches, courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

Artist Carrie Mae Weems (b. 1953) works in photography, text, audio, digital images, and video. Using these media, Weems investigates gender roles, family relationships, and the histories of racism and class, among other topics. Philadelphia Museum of Art, part of Weems's Museum Series, evokes the historical exclusion of African Americans, women, and those without power from art museums. This work positions the museum as a space of power and privilege achieved through financial and cultural capital, a place often perceived as inaccessible or unwelcoming by the powerless. Weems looks at the wealthy's agency and power, both criticizing and affirming the very institutions that display her works.

<

>

x